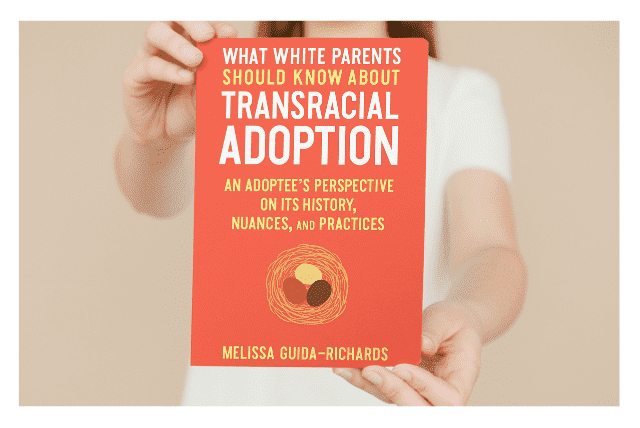

A Book Review: What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption

A Book Review: What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption

An Adoptee’s Perspective on Its History, Nuances, and Practice by Melissa Guida-Richards

Melissa Guida-Richards’ What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption: An Adoptee’s Perspective on Its History, Nuances, and Practices is a mighty, informative manual doubling as a call to action.

Driven by instruction, historical reference points, and personal narrative, the book is a vital resource for all who are touched by adoption, and especially for White adoptive parents (who comprise over 80% of the parents of interracial adoptees in the US).

Adopted from Columbia and raised by her Italian adoptive family in the United States, Guida-Richards did not talk about her birth family’s cultural history or her adoption because her adoption (and the fact that she was Latina) was hidden from her. It was not until she was age 19 that she accidentally happened upon documents revealing her adoption.

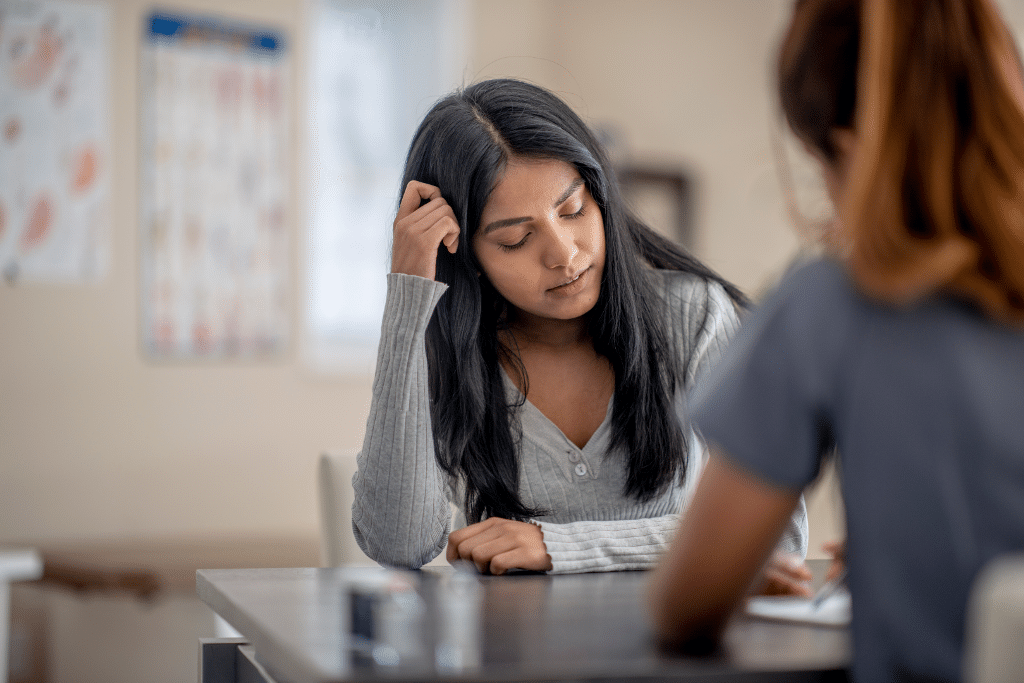

When Richards learned she was adopted, she took the brave step of confronting her parents. A process that she frames as having its peaks and valleys, but one that has ultimately resulted in a healthier relationship between her and her parents (Guida-Richards’ mother wrote the forward to the book).

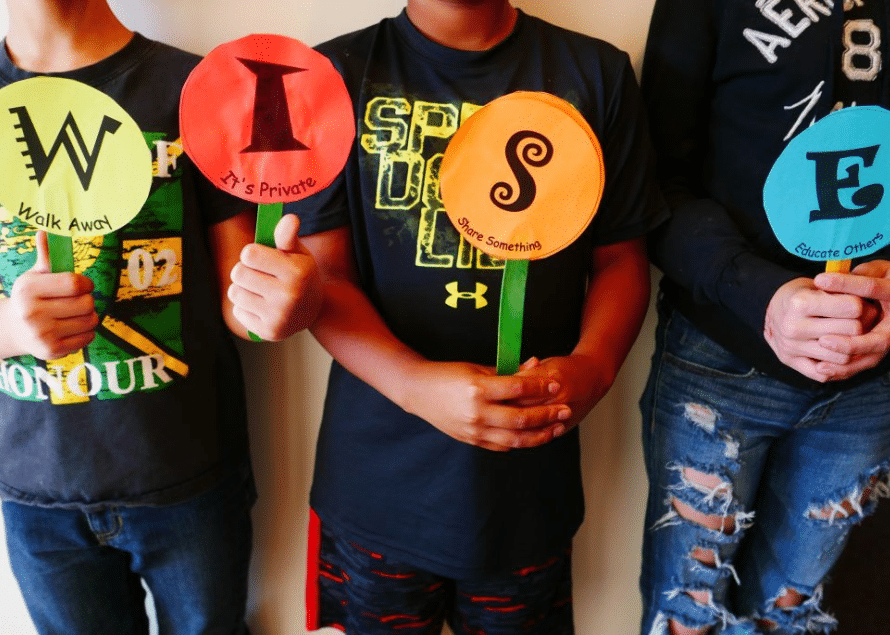

After discovering she was adopted, Guida-Richards learned that many White parents (like her parents) had also used a ‘love is enough’ parenting approach in their homes. This harmful practice promotes the idea that a parent’s unconditional love for their child is enough to foster healthy identity development for them.

The love is enough also approach minimizes (and often erases) the importance of having conversations surrounding race in interracial adoptive households. In addition, it minimizes the importance of honoring birth family connections.

Guida-Richards’ spoke to her parents about how their love is enough approach did not shield her from the racism she experienced. Also, being raised by White parents did not allow ‘their white privilege to transfer to her,’ while documenting the racism she experienced at school and in her community from individuals ‘who frequently identified her as Hispanic’ (despite her parents’ insistence growing up that she was not).

Guida-Richards asserts that her story, and the stories of other adoptees, highlight that there ‘is no one size fits all way to view adoption and that elevating only the positive is a disservice to the adoption constellation‘.

As Guida-Richards states, ‘Adoption is complicated. Adoption is nuanced. Adoption is trauma. And just because it’s beautiful sometimes does not mean that we shouldn’t strive to make it better or that we should fail to acknowledge its flaws.’

Throughout the rest of What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption, Guida-Richards takes readers on a journey that sees her confronting some of the most pressing topics surrounding interracial adoption.

In one example, Guida-Richards addresses racially problematic discourse surrounding interracial adoption that has often presented White parents as ‘saving’ children of color from imagined lives deemed to be of less value than their current lives with adoptive families.

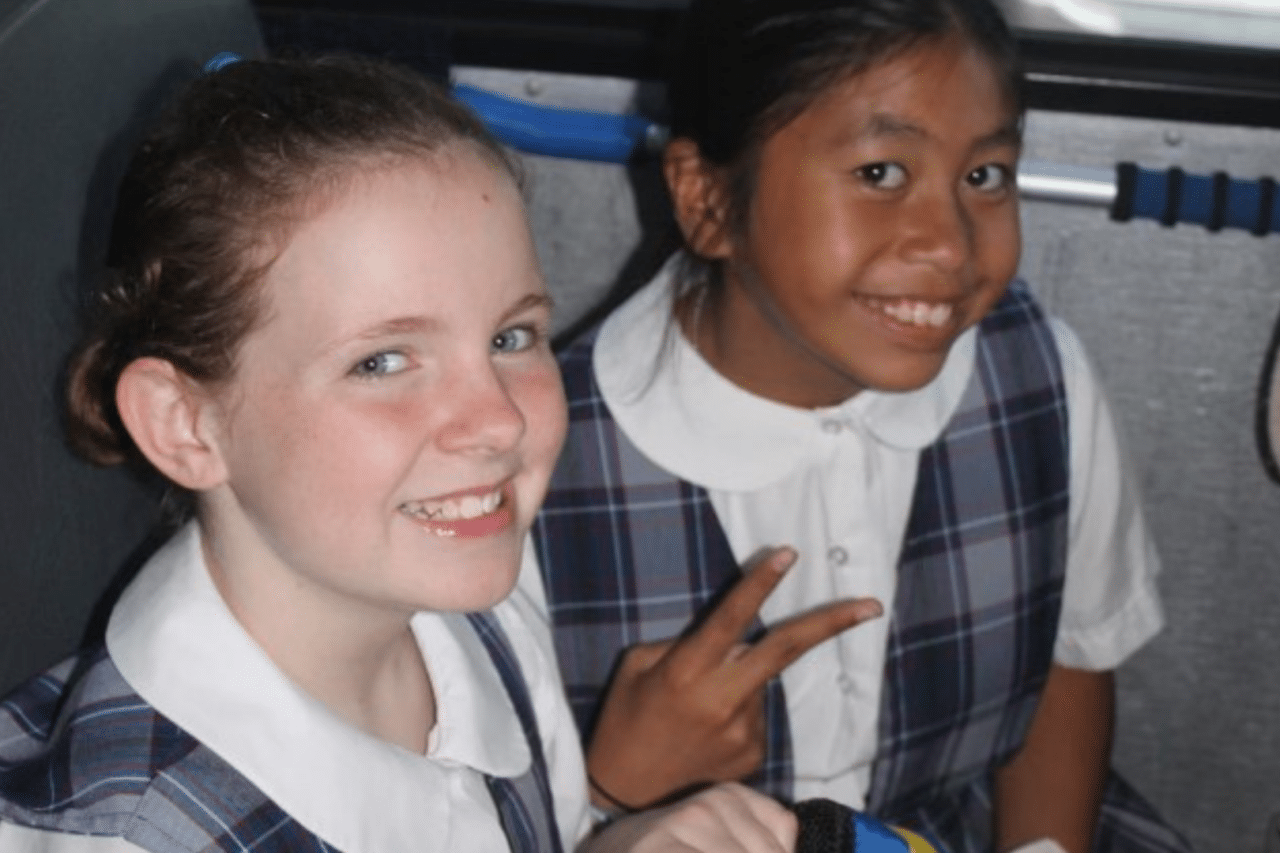

In another, Guida-Richards addresses the racial inauthenticity interracial adoptees frequently experience, as well as the racism they sometimes experience at the hands of their adoptive families. Guida-Richards contrasts this reality with a world that she names as telling interracial adoptees they should be grateful just to be adopted at all.

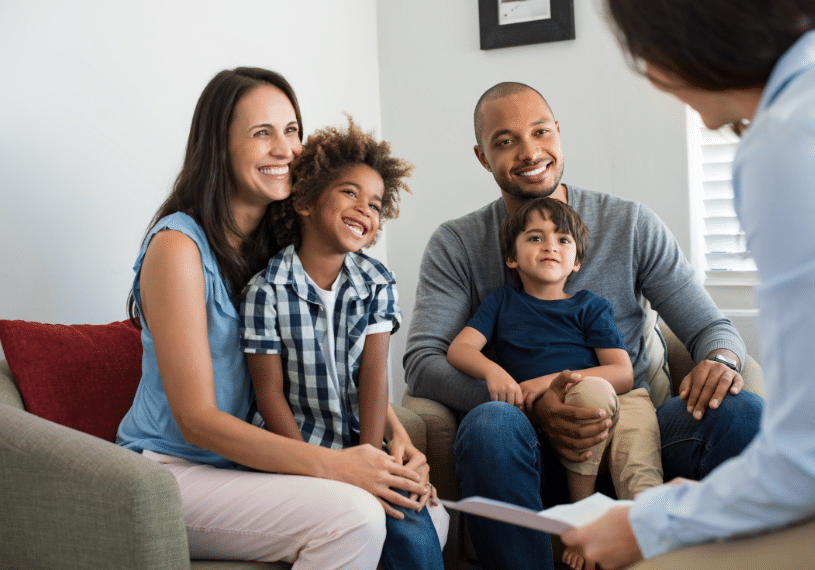

Despite Guida-Richards’ critiques of historical practices in interracial (and especially international interracial adoption), the crux of What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption is not that interracial adoption should or should not exist. Instead, Richards’ conclusion is that ‘transracial adoption will continue to exist.’ As such, Guida-Richards asserts that it is paramount for White parents of interracial adoptees to examine their biases before and after adopting, affirm the cultures of their children, and uplift the voices of adult adoptees of communities of color.

Guida-Richards’ book title indicates that What White Parents Need To Know About Transracial Adoption is meant to help parents. However, Guida-Richards’ messages of adoption positive language, transparency in adoption organizations, legislation supporting international adoptees, promotion of adoptee-centered spaces are essential not only for adoptive parents and adoptees but for the broader systems of adoption to hear as well.

Written by Tony Hynes, MA, C.A.S.E. Training Specialist and author of The Son With Two Moms, Interracial adoptee with LGBTQ identifying adoptive parents, Ph.D. Student at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, studying social connectedness among adult interracial adoptees.

Join C.A.S.E. Training Specialist Tony Hynes & Melissa Guida-Richards, Author of What White Parents Should Know About Transracial Adoption for an Instagram LIVE discussion on Wednesday, Nov. 17th, 7PM EST