Best Practices in Acknowledging Racism for Parents of Black Interracial Adoptees

Best Practices in Acknowledging Racism for Parents of Black Interracial Adoptees

Non-Black parents of Black adoptees (referred to here as interracial adoptees) have an obligation to support their children in ways that speak to the multifaceted nature of their experiences as adoptees, interracial adoptees, and Black people.

This guidance often comes in asking parents to embrace difference by moving to diverse communities or by having friends at their dinner tables who resemble their children and who can serve as mentors to them.

Additionally, parents are told that genuinely seeing their children means honoring their racial/ethnic identities and avoiding colorblind rearing strategies that diminish their children’s ability to explore all of who they are. Parents are also reminded that they are becoming a multiracial family in adopting a Black child.

Given that reality, it is acknowledged that they must educate their family and friends about supporting their children in affirming ways. They are told that at some point, their children will hear what their friends and family understand about racial issues and will feel either supported, not supported, or unsafe, depending upon what they hear from them.

Another critical best practice is for parents to acknowledge racism, which helps Black Interracial adoptees prepare for the racist encounters, systems, and microaggressions they are likely to experience.

Unfortunately, parents of Black interracial adoptees sometimes acknowledge racism in ways that fall short of supporting their children in the ways they need. Understanding how they fall short and acknowledging racism appropriately, will help their children feel more secure in their homes and bodies and encourage them to speak up for themselves when their parents are no longer in their daily lives.

The parents in these families often make the same errors when acknowledging racism that many people make. For instance, they confuse having any level of bias with being racist, making it harder for them to acknowledge bias when they see it, either within their peer groups or within themselves. These mistakes are usually not malicious in intent but still feel dismissive of the current realities Black people in the United States face.

For example, when acknowledging racism, Black people in the United States are frequently told that things are better today than in, say, 1963. That year featured the famous “I Have a Dream Speech” from Martin Luther King Jr., but it was also the same year the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, located in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed. The blast, which happened on a Sunday, injured 20 people, and killed 4: Addie M Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11) were all lost. Before the bombing, the all-Black church had served as a meeting place for Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr.

The church bombing was the third in Birmingham in 11 days after a federal order came down to integrate Alabama’s school system. While that order was a sign of progress at the time, the bombing was a murderous message to the church to stop being what it had been-a haven and a planning ground for the advancement of Black people in the United States.

What I frequently hear from well-meaning people are statements like “we’ve made a lot of progress since then, but there is still a way to go” or “it’s terrible that these things happened, but at least this type of behavior is not tolerated today.”

Fourteen Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) report bomb threats. February 1st is also the first day of Black history month in the United States. The coincidence is not lost on the students and administrators at HBCUs.

In Atlanta, Spellman College student Saigan Boyd said she saw an email about the threat issued by the University. “It was very disturbing … It made me feel as though that I am not safe,” the 19-year-old said. “It makes me realize how there are still these terrorists that are trying to stop minorities from advancing or just getting a simple education from a predominantly Black institution. I’m just ultimately tired of dealing with this level of unsolicited hatred,” she said. “I’m just tired of being terrorized like how my grandparents were.”

At Jackson State University in Mississippi, another HBCU that reported a bomb threat, student Calvert White had this to say, “I’m uneasy,” he said. “HBCUs have a long history of physical threats just because of our existence. I think that the threats aren’t individual or coincidental — that it’s a clear attack on Black students who choose to go to Black schools.”

As of this writing, the FBI has identified the suspected terrorists as persons of interest and hate crimes charges are reportedly being considered.

Few deny that progress has been made in the last 60 years. However, when bomb threats are made towards Historically Black Institutions, or when Black persons are racially profiled and killed while jogging, or when Black churchgoers are systematically murdered in a mass shooting by a white supremacist, “progress” is not what comes to mind. Such incidents continue to happen, underscoring that Black people are still at risk of being targeted, even in times of racial progress.

In 2020, there were 2871 anti-Black hate crimes in the United States, more than tripling the nearest number of hate crimes against the second-highest total for any racial group (869 for anti-White hate crimes).

In addition, Black individuals still experience racial prejudice resulting from subconscious racism.

For example, a teacher who only suspends a Black student when they and their White classmates act out in class.

A peer who refuses to heed a Black friend’s wishes for them not to touch their hair.

Or the friend who casually tells peers that their parents didn’t hire a Black person because they thought their name sounded too “Black” for their White clients, behavior they believe is wrong but appropriate for their parents to enact to protect their business.

Or, in the case of the Black interracial adoptee, the adoptee who is told that their adoptive parents are responsible for how “articulate” they are.

The reality is that without the support of their parents, mentors, and peer allies, Black interracial adoptees are likely to go through these difficult experiences, and countless other experiences like it, alone.

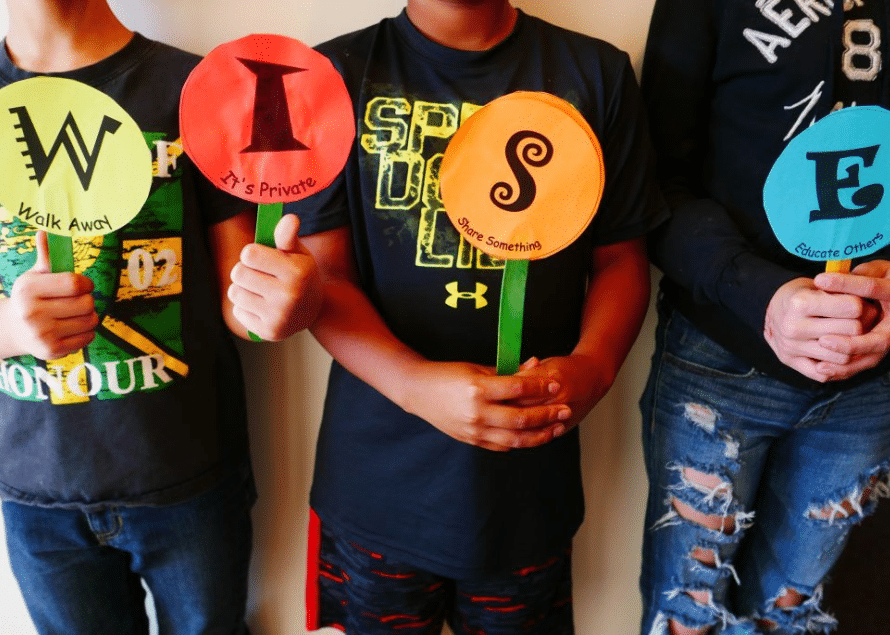

What Parents of Black Interracial Adoptees Can Do

- Talk to your children about racism without using qualifiers (i.e., “it’s better now” or “we have come a long way”). Replace those words with statements like “and that history (or reality) is why I will continue to speak out against racism wherever I see it.” Or “that is why I continue to educate myself on what I can do to fight racism in my community.”

- Acknowledge racial bias that you might possess or have possessed in the past and how you fight against it. Acknowledge that bias is something that we all struggle with, and that to become better, it is important that we fight against the different forms of biases we hold by educating ourselves about where they come from, and about how they frequently represent stereotypes we have been conditioned to believe are real.

- Instill ethnic/racial pride in your child and educate your children about your own ethnic/racial heritage.

- Step back from family members and peers who say racist things (especially after you have attempted to educate them on why their statements are problematic). Your child needs to feel that, at the very least, their family environments will not be places they can expect to hear problematic racial comments.

- Recognize that it is OK not to have THE answer to solving racism.

- Admit that there may be times in Black Interracial Adoptees’ lives where they will encounter racism and that you will support them in figuring out the best next steps to take should/when those incidents arise. It is essential that they feel comfortable sharing their racialized experiences in the world with you.

- Acknowledge the different forms of racism in society (internalized, interpersonal, institutional, structural). Racial epithets and racialized violence are racist, but so are hiring practices that continuously elevate non-Black applicants over Black applicants, for example.

- Explain that prejudice based on race, gender, sexual identity, socioeconomic status, etc., is wrong. Balancing honesty with empathy is a delicate task that parents must strive to achieve.

Resources for Fighting Racism

Written by Tony Hynes, MA, C.A.S.E. Training Specialist and author of The Son With Two Moms, Interracial adoptee with LGBTQ identifying adoptive parents, Ph.D. Student at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, studying social connectedness among adult interracial adoptees.