My Balancing Act: An adoptee social worker in the child welfare world

My Balancing Act: An adoptee social worker in the child welfare world

“Ms. Emily, Ms. Emily!” exclaimed the little girl through the weather door of her foster home. Like most weekdays, I visit the homes of children experiencing foster care and provide an in-home service preparing children for permanency in their birth, kinship, or future adoptive homes.

This witty toddler was the last thing standing between me and the end of a long day. While she colored a blank puzzle, I talked with the foster parents about the importance of familial supports and who the child considers family. They took turns writing the names of their own kin on each small puzzle piece. What was most evident to me was that there was no mention of the child’s birth family anywhere. I brushed this off because surely, they would want to complete a second puzzle to include those missing from the child’s first creation. I was wrong.

Later in the session and with the little girl’s attention waning, I challenged the foster parents to consider birth family relationships post-adoption. This will be her forever home, I thought. It felt naïve of me to not push them to think about the profound absence of birth family from the activity. In no simpler words than this, the foster father staunchly proclaimed, “If we do a good enough job, she will never want to know.” I was taken aback, shifting my focus between this conversation and playful engagement with the child and her parade of stuffed animals. All I wanted to do now was shrink into a corner and avoid the uncomfortable, but I knew I had to confront the abrasiveness hurting my heart at its most primal core.

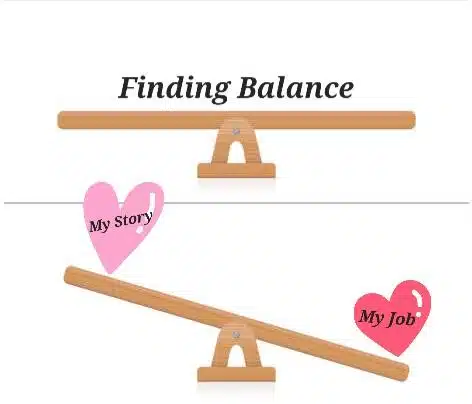

As an adoptee and adoption professional, I traverse a tightrope above the waters of foster and adoptive families hungry for support, advice, and validation. This balancing act is quite literal, with some families appreciating my lived experience and others not so sure of its significance. In this scenario, I had already disclosed my adoptee status to the foster parents in a prior session. I left it at this without telling too much else, afraid of how they would respond to my openness. I also feared my mushiness would invalidate the rapport I had built with these reserved caregivers. The foster parents did not inquire further, and I felt safe and in control of my narrative.

This time though, the foster father’s biting words catapulted me into feelings of unsafety, shock, and sadness. My heart beat rapidly and sank into my chest all at once. Our interaction felt like a slap in the face after some vulnerable self-disclosure. This perspective, I wanted to presume as a new worker in the field, should be nearly extinct by now. Practices of years past, like little to no contact with the birth family after adoptions or colorblindness in transracial placements, were not what I anticipated to encounter- at least not so blindingly apparent. I paused to collect my thoughts before exploring why “good enough” would completely shield this child from the realities of foster care and adoption. Giving this little girl everything, but the answers to her most intimate questions, will probably not quelch the youngster’s innate curiosity to think about what could have been. I was determined to find out why he believed his statement to be an unwavering truth. His reasoning behind what constitutes a “well-adjusted adoptee” was quite narrow. The foster father’s belief was rooted in the experiences of a few children who joined his extended family by adoption. If those kids are fine, why would the child he has cared for since infancy not be too?

My time working with this family stands out to me for a few reasons, but mainly because when I looked into this little girl’s eyes, I saw myself. I saw the information withheld from me until I was in high school. I saw the unawareness of loss and grief. I saw the lack of a foster or adoptive support network to encircle the family and champion the child long-term. Most of all, I saw that they could give the child a wonderful life. The only thing missing was their obliviousness to adoption’s lifelong implications.

This National Social Work Month, I wanted to highlight the uniqueness of working with clients while wearing both my adoptee and social worker hats. Sometimes, wearing two hats at once feels like having a superpower. Other times, it feels like a curse. My emotional investment is a double-edged sword. A tightrope act, even. One wrong move and I am hurt. This is why personal reflection and staff supervision are so important. I parse out my story from their own, knowing that this perspective can still be highly valuable to my work with foster and adopted children. There is an indescribable feeling in being “seen” by others with common stories. I am fortunate to experience this in adoptee-led spaces like the Emerging Leaders Council at C.A.S.E. I hope that my work with clients fosters at least a sliver of what I have felt when surrounded by other adoptees. Simply put by an older child at my agency’s monthly support group, “You’re adopted too? You’re just like me!”