Search and Reunion: Through the Eyes of Adoptees

Search and Reunion: Through the Eyes of Adoptees

When I was 23, I attended an adoptee support group for the first time. I was excited, wondering what the meeting might hold. I had never been around a group of adoptees before and was curious what the conversation would be like. I hoped that the conversation would be enriching, and it was. Around 25 of us sat in a circle, talking about our adoption search and reunion experiences. What many non-adopted people may not realize is how much we often hold back about what it feels like to be adopted, especially when we’re not among others who share that experience. In that circle, there were tears, laughter, and countless stories. Though I’m usually one to offer a comment or two, instead I just listened.

Search and Reunion Brings Mixed Emotions

Their stories were unique, but most of them were tied to one central theme — search and reunion. A 56-year-old adoptee had gone her entire life without knowing her birth family and had just now located an uncle she hoped could connect her with the rest of her family. A 32-year-old had recently located cousins of hers through ancestry DNA and was attempting to find her birth mother. A 47-year-old had found his birth siblings and had now been in contact with them for 5 years.

There was pain in each story, along with a sense of hope, and in some, triumph. Much of the pain in their stories resided in two areas. First, knowing that they had gone so long without knowing these distinct pieces of who they were through seeing their smiles, cultures, and personalities reflected in others who shared their genetic makeup. Another was the complexity of sharing their search for their birth families with their adoptive families. Telling their adoptive parents about their search often brought mixed feelings. What should have been joyful news was sometimes met with blank stares or subdued responses.

Some in the circle asked quietly, “You told your parents?” Others admitted, “I haven’t even told mine I’m searching,” as heads nodded in understanding.

Every Adoptee’s Experience is Different

It was a fascinating experience for me, an adoptee who had an open adoption. I did not feel I had the right to speak. I had been separated from my birth family, but I had the opportunity to grow up knowing my birth sister and my mother. What I did not share with the room, however, was that I had learned I had another sister, a sister who was adopted in a closed adoption, whom I knew nothing about other than her first name, Sophie. I did not learn about Sophie until I was 19, and I did not begin my search for her until I was in my mid-20s. Much like the adoptees in the room, I did not share much about my search for Sophie with my adoptive parents. My story was reflective of the fact that even in open adoptions, search and reunion is still often present in the minds of adoptees. Knowing members of my birth family did not mean I could not mourn or talk about losing them, a sentiment I wish I knew the first night of that support group.

Why Reunion Often Raises More Questions Than Answers

To many, “search and reunion” might sound like a simple two-step process: you search, and you find—or you don’t. But for adoptees, it’s far more layered. The search often leads to more questions that spark new searches. Reuniting with our birth families might be thought of as an entirely wholesome, joyful event—and it sometimes is. However, for those in the circle, reuniting was also difficult. Some faced rejection from their birth parents, who had wanted to keep their adoptions a secret forever. Others described sadness at feeling a sense of difference from their birth families, who were from different geographic, socioeconomic, or cultural backgrounds than they had grown up around.

Searching and Finding Pieces of Themselves

Reunion often became the beginning of searching for pieces of themselves, pieces that they thought they had lost forever.

In many ways, reunion is not the end—it’s the beginning of another kind of search. A search for identity, belonging, and wholeness.

Why Support Matters in the Search and Reunion Journey

The journey of search and reunion is deeply complex. It requires hope, community, and support. I felt all of those things in the room that day. I just wish that the adoptees in that circle—and others like them—felt that same support outside of that space.

I remain hopeful that, as more people begin to understand the emotional realities of adoption, adoptees will feel empowered to share their stories not only in rooms made just for them, but in the wider world too.

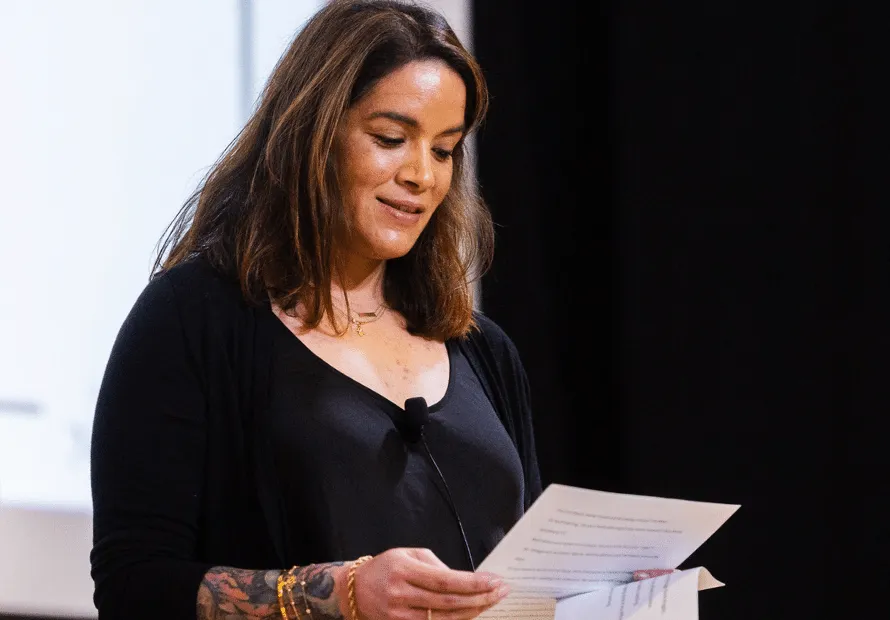

Today, I am honored to provide a space to other adoptees in the Adult Adoptee Support Group at C.A.S.E., a group I started with fellow adult adoptee Rachel Shifaraw to provide a space for other adoptees to share their experiences with search and reunion, identity, and anything else on their hearts. The group is a space for reflection, but more importantly, for community.

There is a special sense of relief in being truly seen by other adoptees. In knowing that our reality is accepted, and understood, with a nod, or a word, and that we are to listen to each other–whenever we are ready to share.

Here are some additional resources you can use to support your search and reunion journey:

- DNAngels: This nonprofit is dedicated to the assistance of individuals seeking to identify their biological parent(s) using DNA interpretation, mapping, and extensive research.

- International Soundex Reunion Registry (ISRR): One of the oldest and largest mutual-consent reunion registries in North America.

- Metro Reunion Registry: A complementary registry supporting adoptees, birth parents, and siblings. Covers all U.S. states, Canada, and over 20 countries with no fee to register. Matches are notified immediately upon entry

- G’s Adoption Registry: A free mutual-consent registry aimed at adoptees and birth families looking to learn about medical history and genealogy.

- Adoptee Hub – Global Birth Search (GBS): Focused on Korean and international adoptees. Provides Hope Registry portal and free DNA kits to qualified matches.

- Foster Club: National network of current/former foster youth that offers leadership development, support communities, and advocacy tools.

- Adoption Mosaic: Offers “Adoptee Voices” panels, support groups, coaching, and educational resources, and is focused on helping adoptees navigate identity, reunion, and healing.

If you’re an adoptee beginning or continuing your search and reunion journey, know this: your feelings are valid, your story matters, and there is a community ready to walk alongside you. Whether you’re just starting to ask questions or are deep in your reunion process, support makes all the difference.

Join our Adult Adoptee Support Group at C.A.S.E. and connect with others who understand the complexities of adoption, identity, and belonging. In this space, you’ll find more than shared stories—you’ll find solidarity, healing, and hope.